The Enlightenment followed on the heels of the Scientific Revolution. The Enlightenment, a term coined by Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), a German idealistic philosopher, was a stark contrast to the Middle Ages (also known as the “Dark Ages”). Literally, enlightenment means to illuminate or to bring lightness into darkness. European society felt that it had emerged from centuries of ignorance, superstition, darkness, blind obedience, tyranny, and faith and into a world of reason, knowledge, truth, and freedom and was marked by the development of a significant amount of new knowledge in all of the subject areas. The rational and empirical approach to political, economic, social, and cultural issues of the 18th century typified the attitudes of the Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment placed a heavy emphasis on science, logic, and reason in order to understand the natural and human world and how to make government and society more fair, free, equitable, and humane. Thanks to the Scientific Revolution, Enlightenment scholars knew that the world ran on natural laws that could be proven by the use of the scientific method. The Philosophes believed that the application of the scientific method, logic, and reason to the human world would solve the political, social, economic, and cultural problems of the day.

![]()

![]()

The Philosophes were more than just philosophers. They were intellectuals and supporters of the principles of the Enlightenment that advocated for political, social, and religious reforms to improve and perfect society. The Philosophes shared a faith in the ideals of the Enlightenment, especially reason and progress. They disputed the idea of the divine right theory and advocated for more democratic political institutions (although they differed on what degree of democracy those institutions should take).

According to Locke in his Two Treatises of Government (1690), people had certain natural

rights, specifically, life, health, liberty and property (and they had the freedom to defend those rights).

Locke believed that people in a state of nature were free and equal, but also selfish and

unrestrained. Therefore, people agreed to surrender some of their rights to form a government

that would create order and protection. Government, then, received powers from the people,

not God (Locke refuted divine right theory). Locke believed that a legitimate government was

instituted by the explicit consent of those governed. If the government did not uphold its side

of the contract by protecting the rights and property of the people as well as providing order,

then the people had the right to amend or abolish the government.

According to Locke in his Two Treatises of Government (1690), people had certain natural

rights, specifically, life, health, liberty and property (and they had the freedom to defend those rights).

Locke believed that people in a state of nature were free and equal, but also selfish and

unrestrained. Therefore, people agreed to surrender some of their rights to form a government

that would create order and protection. Government, then, received powers from the people,

not God (Locke refuted divine right theory). Locke believed that a legitimate government was

instituted by the explicit consent of those governed. If the government did not uphold its side

of the contract by protecting the rights and property of the people as well as providing order,

then the people had the right to amend or abolish the government.

Montesquieu’s main political concepts in The Spirit of Laws (1748) were the separation of

the powers of government and a system of checks and balances. Montesquieu proposed that a government

should be divided into three divisions or branches: 1) a legislative power to make laws; 2) an

executive power to enforce the laws and provide protection; and 3) a judicial power to settle disputes.

Governments that separated their powers were free and democratic. When powers of government were

united, it led to a tyrannical or oppressive government. Montesquieu also proposed a system of checks

and balances, which allowed each division of government to limit the others and maintain an equilibrium

between the different parts of government. Montesquieu believed a government with powers separated

into three divisions and a system of checks and balances would be the best form of government as it

would be free, equitable, and democratic.

Montesquieu’s main political concepts in The Spirit of Laws (1748) were the separation of

the powers of government and a system of checks and balances. Montesquieu proposed that a government

should be divided into three divisions or branches: 1) a legislative power to make laws; 2) an

executive power to enforce the laws and provide protection; and 3) a judicial power to settle disputes.

Governments that separated their powers were free and democratic. When powers of government were

united, it led to a tyrannical or oppressive government. Montesquieu also proposed a system of checks

and balances, which allowed each division of government to limit the others and maintain an equilibrium

between the different parts of government. Montesquieu believed a government with powers separated

into three divisions and a system of checks and balances would be the best form of government as it

would be free, equitable, and democratic.

Voltaire advocated for political and social reforms through a tremendous amount of literary works

(novels, plays, letters, poems, etc.) He criticized both the king (government) and the church.

He opposed the absolute power of the king and the privileged power of the nobility as well as the

power of the church and clergy. As a result of his seemingly constant attack on the king and

church, he was both imprisoned and exiled from France for his beliefs, which only fueled Voltaire

to further promote the ideas of freedom of speech, press and religion.

Voltaire advocated for political and social reforms through a tremendous amount of literary works

(novels, plays, letters, poems, etc.) He criticized both the king (government) and the church.

He opposed the absolute power of the king and the privileged power of the nobility as well as the

power of the church and clergy. As a result of his seemingly constant attack on the king and

church, he was both imprisoned and exiled from France for his beliefs, which only fueled Voltaire

to further promote the ideas of freedom of speech, press and religion.

"écrasez l'infâme" (crush infamy) is a common phrase repeated in Voltaire's writings, in which he refers to the abuses suffered by the people at the hands of the clergy or the royalty.

In his writings, Voltaire criticized the fact that all power rested with the king and the church of France. The divine right theory only reinforced this power – the church taught that the king derived his right to rule from God and the king supported the authority of the church. As long as this system was in place, the nobility and clergy remained in privileged positions over the common people. Therefore, Voltaire was a strong supporter of the separation of church and state. Through his writings, Voltaire, brought to light such issues as censorship (much of his work was banned and he denied authorship of some for fear of persecution), the use of torture to illicit confessions, the absence of trials by jury, the fact that there was no single, uniform code of law, and that judicial appointments were sold to the highest bidder.

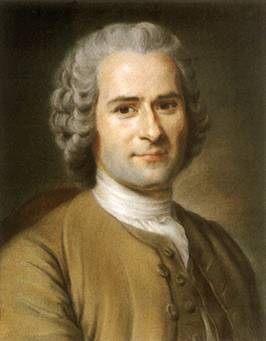

Perhaps Rousseau’s two most important works were Discourse on Equality (1754) and The Social Contract (1762). Rousseau believed that the primitive state of nature was

the ideal. All human beings were created equal and were naturally good and free in that state of

nature. Civilization and the pursuit of power and wealth, especially the acquisition of property,

corrupted man and destroyed freedom and equality. According to Rousseau, the government was created

to correct this political and economic inequality. Rousseau stated that government was a necessary

evil and that it should exist to protect the common good. He believed that the best government would

be a democracy or one controlled by the "general will" of the people (popular sovereignty).

Perhaps Rousseau’s two most important works were Discourse on Equality (1754) and The Social Contract (1762). Rousseau believed that the primitive state of nature was

the ideal. All human beings were created equal and were naturally good and free in that state of

nature. Civilization and the pursuit of power and wealth, especially the acquisition of property,

corrupted man and destroyed freedom and equality. According to Rousseau, the government was created

to correct this political and economic inequality. Rousseau stated that government was a necessary

evil and that it should exist to protect the common good. He believed that the best government would

be a democracy or one controlled by the "general will" of the people (popular sovereignty).

"Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains."

-- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (1762)

![]()

The ideals of the Enlightenment quickly caught on and spread throughout Europe and the Americas. Salons, coffeehouses, debating societies, and literary circles sprang up all over Europe. Many were open to the public, to all social classes and even to women. An extremely wide range of topics were read and discussed in these public places.

The growing attraction to reason and science as well as the increasing acceptance of universalism and secularism gave rise to academies, such as the Royal Society of London and the Academy of Sciences in Paris. These academies placed more emphasis on the sciences (biology, anatomy, botany, astronomy, etc.) and less emphasis on spiritual and religious studies. In reality, only the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie attended the academies, however, the French academies sponsored academic contests that anyone had the opportunity to anonymously (so gender, social class, religious beliefs, wealth, etc. did not play a part in the judging) participate in.

The publishing industry flourished during the Enlightenment period. The number of new and exciting authors increased dramatically, most writing about the ideals of the Enlightenment using various literary forms (essays, poetry, plays, novels, newspapers, journals, books, pamphlets, etc.). Literacy rates were on the rise and more people demanded access to the writings of the Enlightenment intellectuals and philosophes. Even public libraries were open to all, allowing lower classes to participate in the society of the Enlightenment.

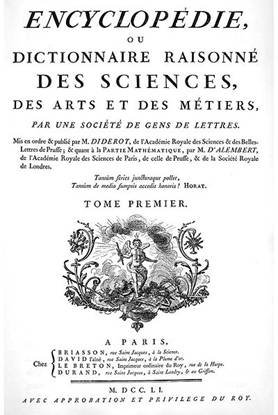

By far, the greatest vehicle for disseminating the ideals of the Enlightenment was the Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une

société de gens de letters or Encyclopédie. The Encyclopédie , published in France between 1751 and 1772, consisted of 28 volumes, which contained

over 70,000 articles and 3,000 illustrations produced by more than 140 authors. These authors,

included notable Enlightenment thinkers, reputable scholars and scientists, all experts in

their field, and skilled tradesmen, describing in intricate detail the processes and tools

of their craft. Denis Diderot (1713-1784), philosopher and writer, and Jean le Rond

d’Alembert (1717-1783), mathematician, and physicist, edited and supervised the publication

of the Encyclopédie. It allowed both the Enlightenment philosophes the

freedom to express their ideas on the most important political, social, technological

developments of the time and allowed any reader of any class, faith, gender, wealth, etc.

the opportunity to obtain, read and analyze for themselves the validity of the Enlightenment

ideals. It also meant that the common people had access to knowledge usually reserved for

the upper classes and that they had the ability to expand their knowledge and participate

in a part of society that again, was usually reserved for the upper classes.

By far, the greatest vehicle for disseminating the ideals of the Enlightenment was the Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une

société de gens de letters or Encyclopédie. The Encyclopédie , published in France between 1751 and 1772, consisted of 28 volumes, which contained

over 70,000 articles and 3,000 illustrations produced by more than 140 authors. These authors,

included notable Enlightenment thinkers, reputable scholars and scientists, all experts in

their field, and skilled tradesmen, describing in intricate detail the processes and tools

of their craft. Denis Diderot (1713-1784), philosopher and writer, and Jean le Rond

d’Alembert (1717-1783), mathematician, and physicist, edited and supervised the publication

of the Encyclopédie. It allowed both the Enlightenment philosophes the

freedom to express their ideas on the most important political, social, technological

developments of the time and allowed any reader of any class, faith, gender, wealth, etc.

the opportunity to obtain, read and analyze for themselves the validity of the Enlightenment

ideals. It also meant that the common people had access to knowledge usually reserved for

the upper classes and that they had the ability to expand their knowledge and participate

in a part of society that again, was usually reserved for the upper classes.

The Encyclopédie brought together vast amounts of knowledge and information with such attention to details as to expand the knowledge base of any reader. It emphasized the theories and thoughts of the Enlightenment while criticizing its opponents (mainly the monarchy and the church). As one of the biggest critics of the Encyclopédie, the Church openly and loudly denounced it. The Encyclopédie included religion as a branch of philosophy (which meant that man could evaluate the authority of religion and the pope). It gave as much attention to the Bible, God, and the human soul as it did to the atmosphere, growing vegetables, and spiders rendering religion on equal footing as the rest of the information included in the Encyclopédie.

![]()

Revolutions in the late 1700s and early 1800s were connected by the common threads of the Enlightenment, especially concerning the rights of man.

The views of the Enlightenment had made their way to American colonies and became the guiding principles of the American Revolution (Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin had both traveled to France, where they were introduced to and maintained contact with the philosophes). The ideas of natural law, social contract, popular sovereignty, secularism, and tolerance were so revered by the political leaders of the time that their influences can be seen in such speeches and works by Jefferson, Franklin, James Madison, George Washington, George Mason, Patrick Henry and John Adams, just to name a few. The result of the American Revolution was the creation of the first major democracy, founded on the philosophies of the Enlightenment.

"The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter. But I should mean that every man should receive those papers and be capable of reading them."

--Thomas Jefferson to Edward Carrington, 1787. ME 6:57

The French, already familiar with the Enlightenment and aware of the success of the

American Revolution (which they participated in), began to question the actions of their

own government. The French Revolution started with the overthrow, which put an end to,

the absolute monarchy and created a new government based on popular sovereignty.

Ultimately, the French Revolution was not as successful as the American, it did leave

an indelible legacy, one of a democratic, egalitarian, secular society, based on natural

rights with a little nationalistic spirit thrown in.

The French, already familiar with the Enlightenment and aware of the success of the

American Revolution (which they participated in), began to question the actions of their

own government. The French Revolution started with the overthrow, which put an end to,

the absolute monarchy and created a new government based on popular sovereignty.

Ultimately, the French Revolution was not as successful as the American, it did leave

an indelible legacy, one of a democratic, egalitarian, secular society, based on natural

rights with a little nationalistic spirit thrown in.

The Enlightenment and the previous revolutions greatly influenced the revolutions in

Latin and South America, especially Haiti, Mexico and the independence movement led by

Simon Bolivar in the northern part of South America. The fact that the common people

stood up for their rights and rebelled against an unjust government that had denied

them their rights was a compelling argument and radical idea for the Latin and South

American revolutionaries. The society of the Spanish colonies consisted of a

multi-dimensional class system, which included a large segment of slaves.

Enlightenment ideas created a need and want for equal rights and freedoms within the

Spanish colonies, which encouraged open rebellion.

The Enlightenment and the previous revolutions greatly influenced the revolutions in

Latin and South America, especially Haiti, Mexico and the independence movement led by

Simon Bolivar in the northern part of South America. The fact that the common people

stood up for their rights and rebelled against an unjust government that had denied

them their rights was a compelling argument and radical idea for the Latin and South

American revolutionaries. The society of the Spanish colonies consisted of a

multi-dimensional class system, which included a large segment of slaves.

Enlightenment ideas created a need and want for equal rights and freedoms within the

Spanish colonies, which encouraged open rebellion.

![]()

The Enlightenment championed change and reform at the expense of the church and the monarchies. It challenged traditional institutions (like the government controlled by ruling families and the Church), customs, and morals. The Philosophes advocated for reforms to create a better society and improve the human condition by applying logic and reason to the human world (much like the thinkers of the Scientific Revolution employed the use of reason on the natural world). The political, social, and scientific ideas of the 17th and 18th centuries gradually overturned many of the most fundamental premises of the medieval worldview. These philosophies and values of the Enlightenment shifted the focus from faith to reason, from religious to secular, from autocracy to democracy, from privileged class to equality, from stagnation to progression. As these ideals of the Enlightenment spread, not just throughout Europe and the Americas, but to the common people as well, it changed from being a hope to a movement, where people were willing to fight for the more preferable, democratic, egalitarian, and liberal society. The Enlightenment resulted in dramatic change in political, economic, social, and cultural thought that forever revolutionized European and American societies.

This page is copyright © 2010-17, P. Niles and C.T. Evans

For information contact cevans@nvcc.edu