![]()

The Peace Conference

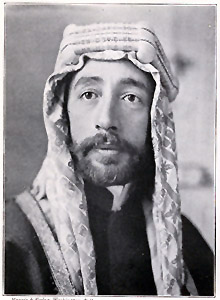

In November 1918, when Prince Feisal boarded His Majesty's Ship Gloucester in Beirut to attend the upcoming peace conference in Paris, he did so in the knowledge that as early as 1915 the British had promised independence to the Arabs in return for a revolt against the Turks. (47) Feisal was aware of, and had accepted, certain limits to Arab claims; a line drawn from Aleppo in the north to Damascus in the south meant exclusion of the Mediterranean coastline as far south as Damascus. The British also had claimed the old Turkish provinces of Basra in the south and Baghdad in the north. (48) Feisal was prepared to accept these provisions, but the details had yet to be worked out. Lawrence was to accompany Feisal to Paris. Officially he was a delegate of the British Government assigned to Feisal as his interpreter.

When Feisal arrived in France, his presence was not appreciated by the French. (49) The Arab claims to Syria did not accord with French designs on the region. Despite past joint Anglo-French communiqués indicating support for Arab independence, the French now insisted on carrying out the details of the Sykes-Picot Agreement and making claim to all the territories that the agreement gave them. (50) When Feisal landed at Marseilles, the French did everything possible to make life difficult for him. They delayed him from reaching Paris, and, instead sent him on a tour of battlefields. Feisal left France temporarily, on 10 December 1918, and traveled to England. There the welcome was warmer, but there he also learned that he might have to accept France as overlord in Syria. He was also reminded that the British were not prepared to consider Palestine a part of any Arab state. (51)

When the Peace Conference opened in January, the French continued to hinder Feisal. They claimed that he was not on the list of official delegates and only after official complaints from the British, did the French grudgingly agree to add him to the list, but only as a representative of the Hejaz. (52)

At the Peace Conference, Feisal enjoyed the support of Lloyd George who wanted France to be excluded from the Middle East as much as possible, Sykes-Picot agreement or no Sykes-Picot agreement. Lloyd George felt that the situation had changed since 1916. (53) With the Russian Revolution underway, the British now wondered, "Was it still desirable to let the French have Mosul?" and "Why do we still need a French buffer zone?" Back in London, Lord George Curzon, Leader of the House of Lords and member of the War Cabinet, described the Sykes-Picot agreement as, "That unfortunate agreement which has been hanging like a millstone round our necks ever since." (54)

Despite the desire to minimize the French presence in the Near East, the British were divided in their own ranks regarding the exact settlement of the region. On the one hand, the Anglo-Indian Office was desperate that Mesopotamia should become a British colony. Those in favor of such a strategy were all for making peace with France regarding the French claim to Syria and for educating Feisal to realize the need for him to accommodate the French. (55) On the other hand, there were those amongst the British Foreign Office delegation who felt strongly that the promises made to the Arabs should be honored, even at the expense of a falling out with France over Syria. (56)

Meanwhile, at the conference, the Americans were impressed by the Emir and his aide. Robert Lansing, the American Secretary of State, wrote, "The vivid picture of this distinguished Arabian that arose in my mind as I thought of him caused me to realize that an unerasable impression had been made upon me by his physical characteristics, his bearing and his dress. … The movements of the Emir Feisal were always unhurried and stately. He moved and spoke with deliberation and dignity." James T. Shotwell, a Canadian-American historian who was part of the U.S. delegation at the conference wrote of Feisal and Lawrence, "I have seldom seen such mutual affection between grown men as in this instance. Lawrence would catch the drift of Feisal's humor and pass the joke along to us while Feisal was exploding his idea." (57) Lawrence was at Feisal's side constantly, resplendent in his own Arab dress. (58)

In his efforts to represent Feisal, Lawrence frequently ignored protocol and went above the heads of his immediate bosses to consult directly with Lloyd George, Clemenceau and Wilson in order to press the Arab cause. His actions were interpreted by many as disrespectful of rank as well as arrogant. Yet driven as he was by a sense of guilt for his self-perceived betrayal of the Arab cause (he felt guilty that he had urged the Arabs to continue fighting against the Turks under false pretenses), (59) Lawrence now sought to make amends and to assuage his own conscience by doing everything in his power to put things right.

In the early days of the conference Lawrence and Feisal sought to present their case for Arab independence anywhere anytime, to anyone who would listen, delegates and pressmen alike, in private rooms and tea salons. They found willing audiences as people were curious about the mysterious yet regal Arab and his English paladin. (60) When not courting their audiences, Feisal and Lawrence busied themselves preparing the statement that would be delivered at the conference. (See Appendix A)

Just as the conference was getting under way, on 20 January 20 1919, The Times newspaper of London quoted Feisal as saying, "The Arabs of this most ancient race…desire to become the youngest independent state in Asia, and they appeal to America as the most powerful protector of the freedom of man." The direct appeal to the Americans and the tone of the language were interpreted as arrogant and assertive by certain of the English delegation and by the French. (61)

Even before the appointed time for the formal presentation of the Arab claims, Lawrence was being urged to tone down the perceived belligerency of the Emir's message. An American delegate to the conference, Stephen Bonsal, (62) at the urging of the Big Four, offered Lawrence the example of Professor Paul Mantoux, the internationally respected economist, political scientist and official interpreter at the plenary sessions. (63) "I see the point and I have the greatest respect for this gentleman," answered Lawrence. "Perhaps he is right; but I cannot follow his suggestion. You see, I am an interpreter, I merely translate. The Emir is speaking for the horsemen who carried the Arab flag across the desert from the Holy city of Mecca to the Holy city of Jerusalem and to Damascus beyond. He is speaking for the thousands who died in that long struggle. He is the bearer of their last words. He cannot alter them. I cannot soften them." (64)

The French had already demonstrated their displeasure that Feisal was even at the conference. They recognized him only as a representative of the Hejaz. From their perspective, he had no claim to Syria. Lawrence's stubbornness in refusing to moderate the tone of Feisal's claims to Syria did nothing to ingratiate him, or Feisal, to those already opposed to the claim.

The Presentation to the Council of Ten

On 6 February, the Hejaz delegation, the members of which were, the Emir Feisal, Colonel Lawrence, Rustum Haider, Emir Abdul Hadi and Nuri Said, (65) was finally invited to present its case to the Peace Conference. As Feisal spoke in Arabic, Lawrence simultaneously translated. This time the words of Feisal and the translation were genuine. Feisal argued that the Arabs wanted, and had earned, the right to self-determination (see Appendix A). The only concession he was prepared to make was on Lebanon and Palestine falling under French and British control respectively. Feisal called upon France and Britain to honor their promises of Arab independence.

President Wilson questioned Feisal about the form that any future mandatory should take. (66) In the exchange that occurred between the two men, Feisal told Wilson that he preferred a single mandatory but that the Arab peoples should be offered the opportunity to decide for themselves whether there should be a single mandatory over them or several. The meeting did not go as the Arab delegation had hoped. Having expected a lengthy exchange of views, the men instead departed the proceedings having merely presented their case and been asked questions that sought to reinforce the colonial aspirations of France and Britain. Despite his exchange with Feisal, President Wilson, according to Lawrence, was reserved and non-committal. In Lawrence's opinion the long delayed interview was simply a formality. Lawrence summed up his feelings thus, "We merely established a ceremonial contact, and that to the Arabs is a great sorrow." (67)

After having listened to the Arab delegation, Clemenceau believed the demands to be extravagant. Added to this opinion, Clemenceau was mindful of the political reality that French politicians (led by Picot) and French public opinion were demanding that the mandatory for Syria be given to the French. He also was mindful of his nation's alleged responsibility to the minority Maronite population in Lebanon. (68)

The French also were indignant at the favorable light in which the Americans appeared to receive Feisal. (69) They decided to bring before the council their own hand-picked Syrians. (70) These French-sponsored Syrians claimed that the Emir was an adventurer who counted for nothing in the Arab world, but was simply in the pay of the English. When this tactic appeared to fail, the French resorted to articles in the local press attacking the notion of Arab independence. Even Lawrence was not immune. One paper wrote that Lawrence "was serving his country, but he would hardly hesitate before doing it a disservice whenever his sacred mission demanded. In fact, he encouraged hopes and passions for independence among the Arabs that cannot fail to become a source of embarrassment for Britain." (71)

Politics Gets in the Way of a Settlement

While the French were sure of what they wanted in the Middle East, the British, as noted earlier, were undecided. One faction (the Anglo-Indian Office) wanted to go back to the provisions of Sykes-Picot and give everything to the French that they wanted. Clemenceau had already agreed with Lloyd George that the British could have Mosul, thereby removing the one stumbling block to the British ambition of establishing Mesopotamia as a new colony. (72) Another British faction felt an obligation to the Arabs. Lloyd George was one of those in the pro-Arab camp. He had delayed the withdrawal of British troops from Syria, on the grounds that it would be unwise to pre-judge the decisions of the Peace Conference, (73) thereby persuading the French that their "ally" was untrustworthy. When Britain suggested that France should take charge of Lebanon, leaving Syria independent under Feisal, it merely exasperated Clemenceau even further.

Another aspect of British diplomacy in the Middle East that affected the Arab cause was the Balfour Declaration and the promises made to Zionists regarding the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Sir Gilbert Clayton, who remained stationed in Cairo throughout the Conference, was chief political adviser to General Sir Edmund Allenby, commander of the Egypt Expeditionary Force. Clayton summed up the British diplomatic dilemma;

We are committed to three distinct policies in Syria and Palestine:-

1. We are bound by the principles of the Anglo-French Agreement of 1916, wherein we renounced any claim to predominant influence in Syria.

2. Our agreements with King Hussein … have pledged us to support the establishment of an Arab state, or confederation of states, from which we cannot exclude the purely Arab portions of Syria and Palestine.

3. We have definitely given our support to the principle of a Jewish home in Palestine and, although the initial outlines of the Zionist programme have been greatly exceeded by the proposals now laid before the Peace Congress, we are still committed to a large measure of support to Zionism.

The experience of the last few months has made it clear that these three policies are incompatible … and that no compromise is possible which will be satisfactory to all three parties:-

1. French domination in Syria is repudiated by the Arabs of Syria, except by the Maronite Christians and a small minority amongst other sections of the population.

2. The formation of a homogeneous Arab State is impracticable under the dual control of two Powers whose system and methods of administration are so widely different as those of France and England.

3. Zionism is increasingly unpopular both in Syria and Palestine where the somewhat exaggerated programme put forward recently by the Zionist leaders has seriously alarmed all sections of the non-Jewish majority. The difficulty of carrying out a Zionist policy in Palestine will be enhanced if Syria is handed over to France and Arab confidence in Great Britain undermined thereby.

It is impossible to discharge our liabilities, and we are forced, therefore, to break, or modify, at least one of our agreements. (74)

For their part, the Americans understood that the Arabs did not want the French in Syria, even though that was where the French insisted they needed to be. (75) From the U.S. perspective, the question was, relatively simple: Should the mandate for Syria be given to Britain or should the United States take on the responsibility? (See Appendix D, Article 22 of the Treat of Versailles for a description of mandates). Wilson already knew, though, that the isolationist policies of the U.S. Senate would not permit American involvement in Syria. (76)

These on-going deliberations between the French, British and Americans had ensured that the meeting on 6 February would produce no resolution. An adjournment was called until 9 February, at which time, Balfour assured all those present, that Sykes would make everything clear. "You see, gentlemen, he knows those Arab lands just as I know Aberdeenshire or, say, Kent." (77) Unfortunately, the meeting on 9 February was postponed because Sykes was unable to attend due to influenza. Yet again, an adjournment was called for, this time until 11 February. On 11 February, Sykes still was not present at the proceedings when the assembled dignitaries were stunned to learn that he had died that very morning; his influenza had turned into septic pneumonia. Yet again, Balfour was forced to call for an adjournment in any discussion of the Arab issue. In so doing, he rebuked Sir Maurice Hankey, the Secretary to His Majesty's War Cabinet, for not preparing to his liking, the documents for the various meetings. (78)

The issue of the settlement of the Middle East fell into an abyss as other items dealing with Germany crowded the Arabs off the agenda of the Conference; it was not going to surface again until 20 March. As the Peace Conference carried on around him (with the coming and going of others with their own causes to advance and other settlements to agree) Lawrence busied himself with writing some 160,000 words describing his exploits in the Arabian Desert. These writings were later published as his book, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom.

The Inter-Allied Commission

On 20 March the French presented their case for the French position regarding Syria. The French Foreign Minister, Stephen Jean Marie Pichon re-stated the terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement as the basis for French claims. Lloyd George and Pichon became embroiled in a discussion regarding the history surrounding the agreement. (79) The dithering of the British and the obduracy of the French caused President Wilson to intervene. He suggested the setting up of an inter-allied commission, comprising American, British, French and Italians, to visit Syria to inquire directly of the people how they visualized the workings of self-determination. (80)

Feisal and Lawrence were delighted at this turn of events. Since January they had been advocating a role for the Americans in the Middle East. Some of the British also were pleased for they saw it as a way of distancing themselves from the situation. The British could remain neutral, confident that the commission would report back that the French were not wanted in Syria, thereby giving Feisal what he wanted. (81)

The French were determined that there would be no commission and continued to be obstinate. They were determined to gain Syria at all costs. Clemenceau suggested that the commission should extend its charge and seek out opinion in Palestine and Mesopotamia as well as Syria. This in turn roused the Zionists in opposition to Palestinian Arabs being consulted on their wishes. The Anglo-Indian Office was also opposed to a commission being sent to Mesopotamia. Within days, an unlikely alliance had formed in vehement opposition to the idea of a commission.

The question of how to administer Syria was inexorably linked to the question of how to administer the whole of what had once been the Ottoman Empire. When Wilson had announced the setting up of a commission, Clemenceau had immediately insisted that any commission should look at Palestine, Mesopotamia and Armenia. (82) Each would require a mandate and each was part of an empire that was, according to Lloyd George, "as much in solution as though it were made of quicksilver." (83) "To annoy the British, Clemenceau slyly suggested that the commission look at Mesopotamia and Palestine as well." (84) And it worked!

The Anglo-India Office met with the French to discuss the issue. (85) Meanwhile the French were refusing to participate in any commission unless the British withdrew their troops from Syria. (86) Mindful of the suspicions that the French already harbored against its closest ally, Lloyd George, "felt that [the French] regarded our officers as the stimulators of the anti-French feeling. It might provoke further unpleasantness if we were to send out our representatives." (87)

Wilson still believed in the need for a commission, despite the obstacles being thrown in the way. He appointed Dr. Henry Churchill King and Charles R. Crane to be the Allied commissioners. (88) The Commission arrived in Damascus on 25 June 1919 for a visit that lasted ten days. (89) The Commission did not report back to the Conference until the end of July, after the peace treaty with Germany had already been signed (on June 28, 1919).

The eventual findings of the commission were that the French were not wanted in Syria. (90) By the time the commission reported in July 1919, however, it was clear that the findings were not going to have any influence on the settlement of the Middle East. The French press had conducted a campaign against the commission, accusing it of being Anti-French and pro-British. The French had also found an ally in the British Anglo-India Office. In the United States a recalcitrant Congress was withdrawing back into the isolationism that had existed before the war and was rejecting the peace treaty and membership in the League of Nations. (91)

A Death in the Family and a Parting of the Ways

During the time taken to establish the Commission, Lawrence had remained in Paris and had even taken the view that a Commission could accomplish more if it stayed in Paris. (92) However, Lawrence was about to receive bad news from home. A telegram arrived on 7 April, stating that his father had pneumonia. Lawrence made two short trips to Oxford as a result of this news. (93) In mid-April, after he had returned from Oxford the second time, Lawrence accompanied Feisal to one last meeting with Clemenceau, prior to returning to Damascus. In it Clemenceau laid out again a proposal for French control over Syria, which Feisal rejected. (94) There was to be no meetings of the minds between the Frenchman and the Arab.

Feisal returned to Syria soon afterwards and, with British troops still in the region, declared himself ruler in Damascus. He set about persuading his fellow Arabs that they should assert their right to independence. In September 1919, however, Britain ordered its garrison out of Syria. Although the results of the King-Crane Commission were not communicated officially to the British Government, Lloyd George had knowledge of the details. (95) When Britain ordered its garrison out of Syria, thereby allowing the French to move in, Feisal, remarked, "Inshallah! (If God wills it!) I shall remain in Damascus." (96)

Feisal had protested the settlement between France and Britain. When he complained to the British that he would not submit to the French, he was curtly referred by the British to the French for any redress.

Economics were now driving the agenda for the British. All pretense of honor and integrity on the part of the British towards the Arabs had evaporated. When Feisal returned to Paris he discovered that French views, which had never favored Arab nationalism, were hardening. A new government was elected in France in November 1919 that was even more unsympathetic to Feisal and his cause than even Clemenceau had been.

After Feisal left Paris in April 1919, Lawrence stayed on a while to concentrate on writing his account of the Arab revolt. Realizing that he needed to return to Cairo to collect papers necessary for his account, he traveled, on 18 May 1919, with a squadron of Handley-Page bombers that had been routed through Paris en-route to Cairo. Unfortunately for Lawrence, the aircraft he was traveling in crash-landed at Rome. He escaped with just a broken collarbone, but two other members of the crew were killed. Lawrence was considered fit enough to resume his journey on 29 May 1919. He traveled on to Athens, where he spent a week and then moved on to Crete, where he decided to visit the ruins of Knossos. It was not until late June 1919 that Lawrence arrived in Cairo.

Meanwhile, his absence from Paris allowed those in the Anglo-India Office to "attack Arab nationalism in general and Lawrence in particular … On June 19, Sir Arthur Hirtzel, of the Anglo-India Office, had written a private note to Lord Curzon, ostensibly on the subject of Arab nationalism: 'The propaganda originates with Feisal and Lawrence, and I am convinced that there will be no peace in the Middle East until Lawrence's malign influence is withdrawn. He is advocating and actively supporting a policy which is contrary to the policy of H. M. Government both in Syria and Mesopotamia'." (97)

Lawrence, having returned to Oxford from Cairo was overcome with dismay when he learned of the attacks against him and Feisal. Even though Lloyd George traveled to Paris in September 1919 to try and settle the Syrian question, and even though Feisal was requested to attend from Damascus, Lawrence was not part of the British delegation. His opponents in the Anglo-India Office had won their argument.

Lawrence was reduced to attacking British foreign policy in the Middle East in the press. In a letter to The Times published on 11 September 1919, he referred to documents that had hitherto remained confidential. (See Appendix B). The letter prompted an editorial in response from the paper. (See Appendix C.) In his letter Lawrence argued that no incompatibility existed between the promises made to Hussein in 1915, the Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 and other declarations. He wrote, "I can see no inconsistencies or incompatibilities in these four documents, and I know nobody who does." (98)

Before Feisal had arrived in Paris in September 1919, Lloyd George had concluded the deal to withdraw British troops from Damascus. (99) The only reason for him being there was to be told of the decisions of the British and French Governments. He was presented with a fait accompli. However, it was one that Lawrence was pleased with.

In his elation, Lawrence drafted a letter to Lloyd George which read: 'I must confess to you that in my heart I always believed that in the end you would let the Arabs down:- so that now I find it quite difficult to know how to thank you. It concerns me personally, because I assured them during the campaigns that our promises held their face value, and backed them with my word, for what it was worth. Now in your agreement over Syria you have kept all our promises to them, and given them more than perhaps they ever deserved, and my relief at getting out of the affair with clean hands is very great. If ever there is anything I can do for you in return please let me know. My first sign of grace is that I will obey the F.O. and the W. O. and not see Feisal again. (100)

The Arabs though, as detailed in the King-Crane report, were not happy at having a French presence in Syria. When Feisal returned home from Paris in November 1919, he was of a mind to declare full independence for Syria, which he finally did on 7 March 1920. The Syrian Congress (101) declared Feisal, King of Syria, a Syria that included Lebanon and Palestine in the west and that stretched all the way to the Euphrates in the east. France reacted, as expected, with force, their troops having been on the ground in Syria since the previous November, and demanded unconditional acceptance of their mandate. By 24 July 1920, the reign of King Feisal was over. He was allowed to move into exile in Italy, and the French had their mandate in Syria.

Read the postscript.